The U.S. Department of Defense is making an uncommon move into industrial territory, taking a 40% stake in a planned $7.4 billion mineral smelter in Tennessee through a partnership with Korea Zinc Co., Ltd. (KRX: 010130). It is not often that the government involves itself directly in heavy industrial projects, but this one sits at the crossroads of national security, economic policy, and the long-term aim to rebuild critical mineral capacity at home.

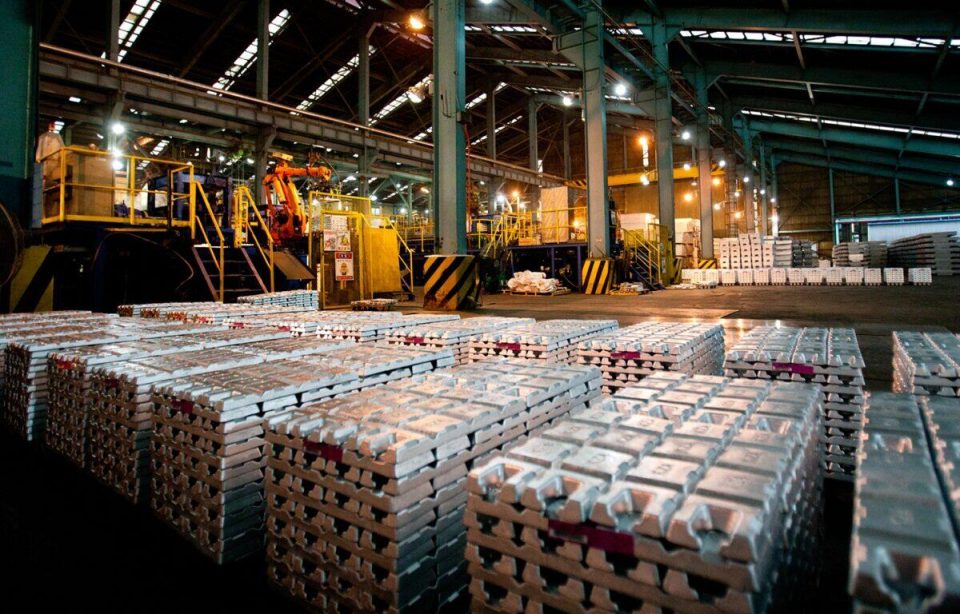

The smelter will refine key minerals essential for electric vehicles, clean energy technologies, and military components. The U.S. Commerce Department said it could produce up to 540,000 tons of material annually, a significant capacity in a country that has watched much of its refining industry move overseas. Reuters, which first reported the deal, noted that Korea Zinc will issue about $1.9 billion in new shares to a joint venture controlled by the U.S. government and unnamed U.S.-based strategic investors. Together, they will hold approximately 10% of Korea Zinc once the agreement closes.

This investment tells a bigger story than just metal production. It reflects how the U.S. is methodically reshaping its industrial base to be less reliant on China, which currently dominates global mineral refining. The partnership is part of a broader federal agenda that blends defense priorities with industrial policy, using financial stakes and incentives to jump-start industries once considered too capital-heavy to thrive on American soil.

Zinc might seem like an unlikely place to make such a statement, but the choice is deliberate. The U.S. has not built a large-scale zinc smelter since the mid-1970s, when the last major facility opened in Clarksville, Tennessee. That facility, once one of the world’s leading primary zinc producers, shut down operations in 2001 amid high energy costs and global market pressures. Since then, the U.S. has imported most of its refined zinc, largely from Canada and South Korea. Decades of offshoring left domestic experts, infrastructure, and supply networks to wither. The new Tennessee facility revives that capacity after almost half a century of absence.

The Defense Department’s involvement signals how critical the government views this shift. Rarely does it commit funds to industrial ventures that are not strictly defense manufacturing projects. But as global competition for metals intensifies, the line between civilian and military supply chains has blurred. Building refining capacity at home could reduce exposure to supply shocks or export controls from countries that dominate metal processing markets.

Beyond the zinc facility, Washington is applying similar logic elsewhere. The U.S. has backed projects to expand lithium and nickel refining in Nevada and Michigan, and supported rare earth element processing partnerships with Australia. Each initiative reflects the same underlying principle: access to critical materials determines future competitiveness in both clean energy and defense manufacturing. These are not short-term subsidies, but strategic investments designed to build domestic capacity that lasts beyond a market cycle.

For Korea Zinc, one of the world’s largest non-ferrous metal producers, this partnership also diversifies its geographic footprint. The company brings technical and operational expertise that the U.S. has not maintained at scale for decades. In turn, American investors and the federal government bring stable policy backing, capital, and a growing domestic demand base. The result is a mutual dependency built on shared interest rather than convenience.

The project also aligns with the political realities of industrial revival. Building new smelters is expensive, energy-intensive, and usually tangled in environmental scrutiny. The Tennessee site represents a calculated compromise: a region with industrial heritage, available infrastructure, and relatively favorable permitting conditions. Still, success will depend not only on construction milestones but also on global mineral prices and how rapidly downstream industries, from automotive to defense, absorb the output.

The Tennessee smelter is more than a new plant. It is a test of whether the U.S. can rebuild the kind of industrial ecosystems it once took for granted. The scale of the commitment, both financially and politically, shows how integral mineral refining has become to the broader debate over economic sovereignty. If it works, it will not just redefine zinc production, but the confidence that the U.S. can again produce what it needs within its borders.