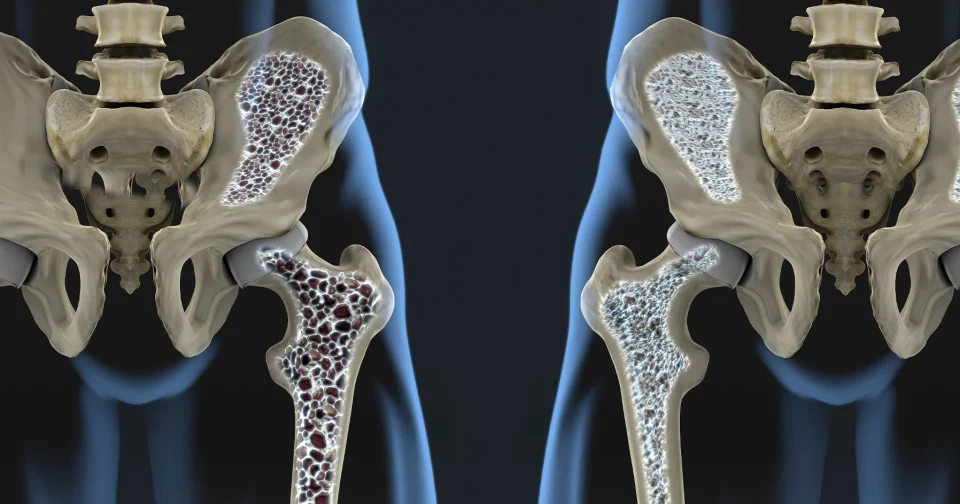

Imagine your bones as a living construction site, constantly balancing build-up and breakdown to stay strong. Osteoblasts act as the builders here, specialized cells that lay down new bone material by secreting a protein-rich matrix that hardens with minerals like calcium and phosphate. They work in tandem with osteoclasts, the demolition crew that clears out old tissue, ensuring bones adapt to stress and repair themselves throughout life. This dynamic keeps skeletal health in check, but when osteoblasts falter, conditions like osteoporosis emerge, where bones grow porous and fragile, raising fracture risks especially in older adults.

Researchers from the University of Leipzig in Germany and Shandong University in China recently zeroed in on a specific player in this process: the cell receptor GPR133, also called ADGRD1. They found it plays a pivotal role in osteoblast function, helping these cells sense mechanical forces and respond by ramping up bone formation. Variations in the GPR133 gene had already hinted at links to bone density differences across people, so the team dug deeper into the protein it produces. Their work, published in a peer-reviewed journal, shows GPR133 activates inside osteoblasts when bones face tension, like during weight-bearing exercise, triggering signals that boost the cells’ matrix-building activity.

What makes this finding stand out is how GPR133 ties into everyday mechanics. The receptor senses stretch or pressure on bone surfaces, much like a sensor detecting load on a bridge, and converts that into chemical messages within the osteoblast. Experiments with mouse models and human cells revealed that without GPR133, osteoblasts produce less bone matrix, leading to weaker density overall. Activating it artificially, though, enhanced bone formation even in lab dishes, suggesting targeted drugs could mimic this effect. The study also connected the dots to exercise: mechanical loading naturally stimulates GPR133, explaining why activities like walking or resistance training help maintain bone mass.

For osteoporosis patients, this opens practical doors. Current treatments often focus on slowing breakdown by osteoclasts with drugs like bisphosphonates, but they carry side effects such as jaw issues or unusual fractures. Targeting GPR133 shifts emphasis to boosting osteoblasts directly, potentially reversing density loss rather than just halting it. Combining receptor-activating compounds with exercise could amplify results, as the study hints at synergy between mechanical cues and pharmacological nudges. Early data from cell and animal tests show denser trabecular bone, the spongy type prone to weakening in osteoporosis.

Pharmaceutical developers might pursue this for treatment, given that osteoporosis affects millions globally and accounts for billions in healthcare costs each year. While GPR133-specific drugs have not yet entered development, the growing clarity around the mechanism could accelerate preclinical research. Clinical trials would need to evaluate safety in humans, focusing on effective delivery to bone cells without off-target effects. Exercise remains essential, as it naturally activates the receptor and could serve as a low-cost complement to future therapies.

This receptor discovery reframes bone health as a mechanically tuned system ripe for intervention. Osteoporosis no longer seems just a wear-and-tear inevitability; it becomes a targetable imbalance in cellular signaling. As research progresses, expect more on how GPR133 agonists pair with lifestyle tweaks to fortify bones long-term. Business watchers in biotech will track this space closely, since effective treatments could reshape markets for skeletal drugs.