The United States and Taiwan have quietly entered a new phase in their economic relationship, and semiconductors sit at the center of it. At its core, the agreement trades lower tariffs for long term commitments to build advanced chip capacity on U.S. soil, with Taiwan’s technology sector pledging at least $250 billion in new investment. For business viewers who do not follow trade policy day to day, this is less about headline numbers and more about how industrial strategy and tariff policy are being tied together.

Under the deal, Taiwanese chip and technology companies have agreed to invest a minimum of $250 billion in production capacity inside the United States, ranging from advanced fabrication plants to supporting technology facilities. That headline figure is backed by an additional $250 billion in credit guarantees from the Taiwanese government, which is intended to lower financing costs for companies that choose to build in the U.S. rather than expand solely at home. The projects will not all arrive at once, and officials have not set a strict timeline, which means this capital is likely to flow over many years as firms line up construction, permits, and equipment.

On the U.S. side, the trade off comes through tariffs. Washington has agreed to limit so called reciprocal tariffs on imports from Taiwan to a ceiling of 15%, down from previous rates that reached about 20% on many goods. In specific sectors, the deal goes further, committing to a zero reciprocal tariff on generic pharmaceuticals, their ingredients, aircraft components, and certain natural resources that cannot be sourced reliably at home. For Taiwanese exporters, this offers more predictable access to the U.S. market, while for U.S. buyers in health care, aerospace, and materials, it lowers input costs that had been rising under earlier tariff rounds.

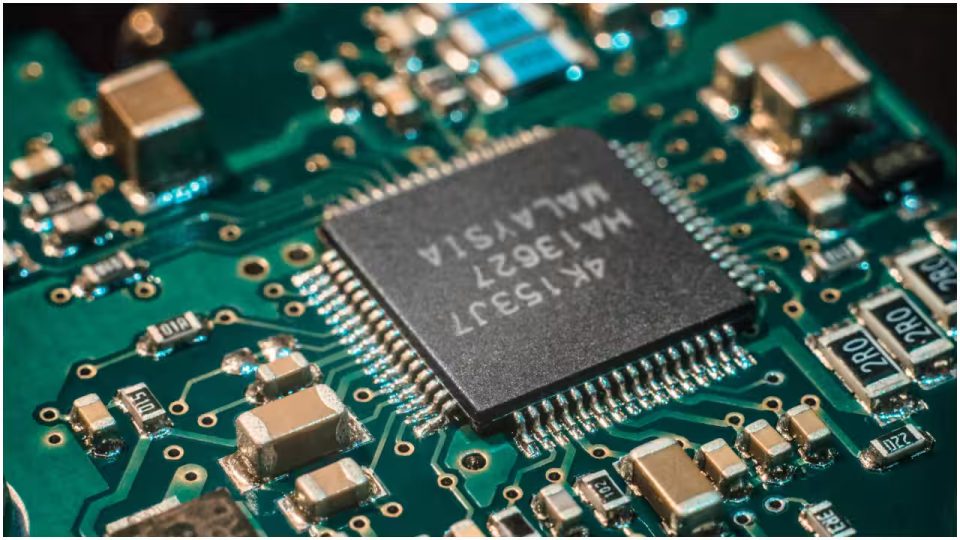

Semiconductors are where the agreement becomes more than a conventional tariff cut. Taiwan already dominates global contract chip manufacturing through firms like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, and the U.S. has spent years worrying about how much of its chip supply depends on factories located an ocean away and close to geopolitical flashpoints. By linking future tariff treatment to investment decisions, U.S. policymakers are trying to pull a meaningful slice of that capacity onto American soil, so that at least part of the supply chain is closer to key customers in sectors such as artificial intelligence, defense, and cloud computing.

The agreement also addresses how Taiwanese firms can move equipment and inputs while their U.S. plants are still being built. Companies that commit to constructing semiconductor production facilities in the United States will be allowed to import goods up to a multiple of the planned production capacity of those sites during the construction phase with relief from certain national security-based tariffs such as those imposed under Section 232. Once the facilities are operational, they will still be able to import more than their U.S. output on favorable terms, though at lower multiples than during construction, which is meant to smooth the transition from offshore production to a mixed onshore and offshore model.

For Taiwan, the calculation is not only about access to the U.S. market. The island’s economy is deeply tied to global electronics cycles and investing directly in the United States spreads both risk and political exposure. By supporting companies with large credit guarantees, the Taiwanese government signals that it wants its national champions to remain central players in the global supply chain, even as large markets like the U.S. emphasize local production for economic security reasons.

From a U.S. policy perspective, the deal sits alongside domestic subsidy efforts such as the CHIPS Act, which provides tens of billions of dollars in incentives for semiconductor manufacturing and related investments. Where subsidies try to pull investment through grants and tax credits, this agreement adds another lever by adjusting tariffs in favor of countries that are willing to put long lived assets and jobs inside the U.S. rather than simply exporting finished chips. For businesses, this creates a more complex environment in which trade policy, industrial policy, and corporate capital allocation are all intertwined.

The key takeaway is that this is not a short term trade headline, but a structural shift in how the U.S. and Taiwan manage one of the most critical supply chains in the modern economy. If the investments materialize as promised, the result will be a growing network of Taiwanese owned semiconductor assets in the United States, supported by tariff rules that reward building capacity rather than simply shipping product across the Pacific.